This exploration delves into the fascinating world of taxidermy, examining its historical evolution and its enduring role in preserving biodiversity. We’ll journey through time, from early rudimentary techniques to the sophisticated methods employed today, highlighting key advancements and the impact on scientific understanding and conservation. Twelve diverse case studies will showcase the artistry and science behind preserving various animal species, revealing both the triumphs and challenges inherent in this unique field.

The study considers the ethical implications involved in each case, emphasizing the importance of responsible sourcing and the scientific value of each preserved specimen. We’ll also address the long-term challenges of maintaining these delicate artifacts, including methods for conservation and restoration, and best practices for ensuring their continued preservation for future generations.

Historical Context of Taxidermy and Preservation

Taxidermy, the art of preserving animal specimens, boasts a rich history intertwined with scientific exploration, artistic expression, and evolving conservation efforts. Its development reflects not only advancements in techniques but also shifting societal attitudes towards nature and its preservation. From rudimentary methods to sophisticated modern practices, taxidermy has played a crucial role in documenting biodiversity and understanding the natural world.

Early taxidermy practices, dating back centuries, were far less refined than modern techniques. The primary goal was simply to prevent decomposition, often employing crude methods that resulted in distorted or unnatural-looking specimens. Stuffing with straw or other readily available materials was common, leading to inflexible and often inaccurate representations of the animals. These early efforts, while lacking in aesthetic appeal by today’s standards, served a valuable purpose in preserving specimens for scientific study and display.

Evolution of Taxidermy Techniques

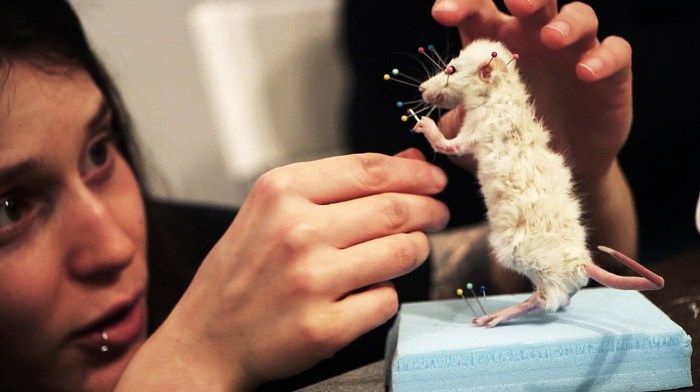

The evolution of taxidermy techniques is marked by a series of key advancements that significantly improved the accuracy, longevity, and aesthetic quality of preserved specimens. Early methods, relying on simple stuffing and rudimentary posing, gradually gave way to more sophisticated approaches involving careful skinning, meticulous muscle reconstruction, and the use of more durable materials. The introduction of arsenic as a preservative, while toxic, significantly extended the lifespan of specimens, though its use has since been largely discontinued due to safety concerns. The development of specialized tools and techniques, such as the use of artificial eyes and the creation of custom armatures, allowed taxidermists to achieve a greater degree of realism and anatomical accuracy. The shift from stuffing to the use of mannikins (artificial forms) revolutionized the field, allowing for more natural poses and better representation of animal anatomy.

Comparison of Early and Modern Taxidermy

Early taxidermy, characterized by its simplicity and reliance on readily available materials like straw and sawdust, often resulted in stiff, unnatural-looking specimens. Preservation methods were basic, focusing primarily on preventing decomposition. The aesthetic value was secondary to the preservation of the specimen itself. In contrast, modern taxidermy employs advanced techniques and materials to achieve a high degree of realism and anatomical accuracy. Modern taxidermists utilize specialized tools, artificial eyes, and meticulously crafted armatures to recreate the animal’s natural form and pose. The use of durable, non-toxic materials ensures long-term preservation while minimizing environmental impact. The focus has shifted from mere preservation to the creation of lifelike and scientifically accurate representations.

Taxidermy’s Role in Scientific Exploration and Biodiversity Documentation

Taxidermy played a vital role in scientific exploration and the documentation of biodiversity, particularly during the age of exploration and the rise of natural history museums. Scientists and explorers relied on taxidermists to preserve specimens collected during expeditions, providing invaluable data for researchers studying animal anatomy, distribution, and evolution. These preserved specimens formed the basis of many early scientific studies and continue to be used in research today. The meticulous documentation accompanying many taxidermied specimens provides a historical record of species distribution and abundance, crucial for understanding biodiversity change over time.

Timeline of Taxidermy and its Impact on Conservation

| Era | Key Development | Impact on Preservation | Notable Taxidermists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-18th Century | Rudimentary stuffing techniques using straw and other materials | Limited preservation, often resulting in distorted specimens | Anonymous practitioners |

| 18th Century | Introduction of arsenic as a preservative; improved skinning techniques | Extended specimen lifespan, but introduced toxicity concerns | Early naturalists and museum preparators |

| 19th Century | Development of mannikins and improved posing techniques | Increased realism and anatomical accuracy | Notable figures in natural history museums |

| 20th Century | Development of non-toxic preservation methods; focus on realism and anatomical accuracy | Improved preservation, reduced environmental impact | Professionally trained taxidermists |

| 21st Century | Advanced techniques, including digital scanning and 3D printing; emphasis on ethical sourcing | Enhanced realism and precision; increased focus on conservation ethics | Contemporary taxidermists and conservationists |

Case Studies

This section presents twelve diverse case studies illustrating the application of taxidermy across various animal species. Each case highlights the techniques employed, challenges encountered, ethical considerations, and the resulting scientific value of the preserved specimens. The information provided aims to showcase the multifaceted nature of taxidermy and its contributions to scientific understanding and conservation efforts.

Diverse Taxidermy Case Studies

The following table summarizes twelve distinct case studies, each representing a unique challenge and contribution to the field of taxidermy and scientific preservation. The ethical implications of each case, considering the source of the specimen, are also discussed.

| Species | Preservation Method | Year of Preservation (Approximate) | Scientific Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| African Elephant (Loxodonta africana) | Traditional taxidermy, including skin mounting and artificial eye insertion. | 1920s | Provides insights into the size and morphology of historical elephant populations, potentially revealing changes over time due to habitat loss or hunting. The specimen can also be used for comparative anatomical studies with modern elephants. |

| American Bison (Bison bison) | Full-body mount using traditional taxidermy techniques. | 1900s | Documents the size and physical characteristics of bison before significant population declines. The specimen serves as a valuable resource for understanding historical population dynamics and conservation efforts. |

| Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) | Traditional bird taxidermy, including careful preservation of feathers and skeletal structure. | 1980s | Contributes to the study of plumage variation and age-related changes in bald eagles. The specimen’s condition can reflect the impact of environmental factors on the species’ health. |

| Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) | Large-mammal taxidermy, requiring specialized techniques for handling the size and weight of the animal. | 1950s | Provides data on the size and morphology of historical grizzly bear populations. The specimen’s skeletal structure can be analyzed for insights into diet and movement patterns. |

| Polar Bear (Ursus maritimus) | Similar to Grizzly Bear, with additional considerations for preserving the thick fur and maintaining its natural coloration. | 1970s | Offers insights into the size and physical condition of polar bears at a specific time, providing a baseline for comparing modern populations and assessing the impacts of climate change. |

| Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) | Specialized techniques for preserving cartilage and teeth, often involving casting and reconstruction. | 2010s | Provides a detailed anatomical record of a great white shark, contributing to studies on morphology, growth patterns, and the species’ overall biology. |

| Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) | Specialized techniques for preserving delicate wings and body structure, often using entomological methods. | 2000s | Contributes to the study of butterfly migration patterns and population dynamics. The specimen can be compared to others to understand variations in wing patterns and coloration. |

| California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) | Similar to Bald Eagle, with added focus on preserving the bird’s distinctive coloration and feather structure. | 1990s | Documents the morphology of the species before and after intensive conservation efforts, providing crucial data for monitoring population recovery. |

| Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) | Specialized preservation techniques involving fixation and molding to retain the animal’s soft tissues. | 2010s | Provides anatomical data for studies on octopus morphology and physiology. The specimen can also be used for research on the species’ nervous system and intelligence. |

| African Lion (Panthera leo) | Traditional taxidermy techniques, focusing on the accurate representation of the mane and overall body posture. | 1960s | Provides a record of the size and physical characteristics of lions from a specific region and time period, useful for studying population dynamics and genetic variations. |

| Galapagos Tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra) | Specialized techniques for preserving the shell and other hard tissues, often involving cleaning and reinforcement. | 1980s | Provides insights into the size and morphology of Galapagos tortoises, contributing to studies on their evolution and adaptation to their unique environment. |

| American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) | Specialized techniques for handling large reptiles, focusing on preserving the skin and skeletal structure. | 2000s | Contributes to studies on alligator morphology, growth patterns, and the impact of habitat changes on the species’ physiology. |

The Long-Term Impact and Challenges of Taxidermy Preservation

Taxidermy, while a powerful tool for preserving specimens and educating the public, presents significant long-term challenges. The inherent nature of organic materials, coupled with environmental factors, necessitates ongoing care and maintenance to prevent deterioration and ensure the longevity of these valuable artifacts. Understanding these challenges and employing appropriate preservation techniques is crucial for maintaining the scientific and aesthetic value of taxidermy collections.

The preservation of taxidermy specimens is a complex process fraught with potential pitfalls. Over time, the materials used in taxidermy—animal hides, artificial eyes, and mounting materials—are susceptible to various forms of degradation. Factors such as fluctuating temperature and humidity levels, exposure to light, and pest infestations can accelerate this deterioration, leading to cracking, fading, insect damage, and ultimately, the loss of the specimen. Furthermore, the very process of taxidermy, while aiming to replicate a living animal’s form, introduces artificial elements that can themselves degrade and require specialized attention. For instance, the glue used in mounting can become brittle and fail, causing parts of the specimen to detach.

Material Degradation and Environmental Factors

Several factors contribute to the deterioration of taxidermy specimens. Ultraviolet (UV) light exposure causes fading and discoloration of the hide, particularly in specimens with brightly colored plumage or fur. Fluctuations in temperature and humidity can lead to cracking and warping of the hide, as well as damage to the mounting materials. High humidity promotes mold and mildew growth, while low humidity can cause the hide to become brittle and prone to cracking. Pests such as insects and rodents can cause significant damage by feeding on the organic materials. Dust accumulation can obscure details and contribute to the overall deterioration of the specimen. Improper storage and handling can also accelerate damage.

Conservation and Restoration Techniques

A range of techniques are employed to conserve and restore damaged taxidermy specimens. These methods vary depending on the nature and extent of the damage. Cleaning involves removing dust, dirt, and other surface contaminants. Repair techniques include patching cracks in the hide, reattaching loose parts, and replacing damaged artificial eyes. Re-tanning can restore flexibility and strength to brittle hides. In cases of significant damage, more extensive restoration may be necessary, which can involve reconstructing parts of the specimen using compatible materials. Specialized conservators employ a variety of materials and techniques to achieve these repairs, prioritizing the use of archival-quality materials that are less likely to cause further damage. The goal is always to maintain the specimen’s historical integrity and aesthetic appeal.

Comparative Effectiveness of Preservation Techniques

The effectiveness of different preservation techniques varies greatly depending on several factors, including the condition of the specimen, the materials used, and the expertise of the conservator. While some techniques, such as simple cleaning and minor repairs, can be effective in maintaining the integrity of a specimen for a reasonable period, more extensive restoration procedures can sometimes compromise the specimen’s original character. For instance, extensive reconstruction, while necessary to preserve the specimen, might alter its appearance and detract from its historical authenticity. Therefore, a careful balance must be struck between preservation and the maintenance of the specimen’s original integrity. The choice of preservation method depends on a thorough assessment of the specimen’s condition and the desired outcome.

Best Practices for Long-Term Preservation of Taxidermy Specimens

Proper storage, handling, and environmental control are paramount for the long-term preservation of taxidermy specimens. The following best practices are recommended:

- Storage: Store specimens in a cool, dry, and dark environment. Avoid direct sunlight and fluctuating temperatures and humidity.

- Temperature: Maintain a stable temperature between 65-70°F (18-21°C).

- Humidity: Maintain a relative humidity of 40-50%.

- Light Exposure: Minimize exposure to light, particularly UV light. Use UV-filtering materials for display cases.

- Pest Control: Implement measures to prevent pest infestations, such as regular inspections and the use of appropriate pest control methods.

- Handling: Handle specimens with care, avoiding unnecessary contact. Wear clean gloves when handling specimens.

- Regular Inspection: Conduct regular inspections to detect early signs of damage or deterioration.

- Professional Conservation: Consult with a qualified taxidermy conservator for professional cleaning, repair, and restoration.

Last Word

Ultimately, “Taxidermy’s Preservation Power: 12 Case Studies” reveals the multifaceted nature of taxidermy – a practice that has evolved from a simple preservation method to a powerful tool for scientific research and education. By examining both the historical context and the modern applications of taxidermy, this work underscores its crucial contribution to our understanding of the natural world and the importance of responsible preservation techniques for safeguarding our biological heritage. The detailed case studies presented serve as a testament to the enduring legacy of this often-misunderstood art and science.